performance; artist’s book (published in 2025)

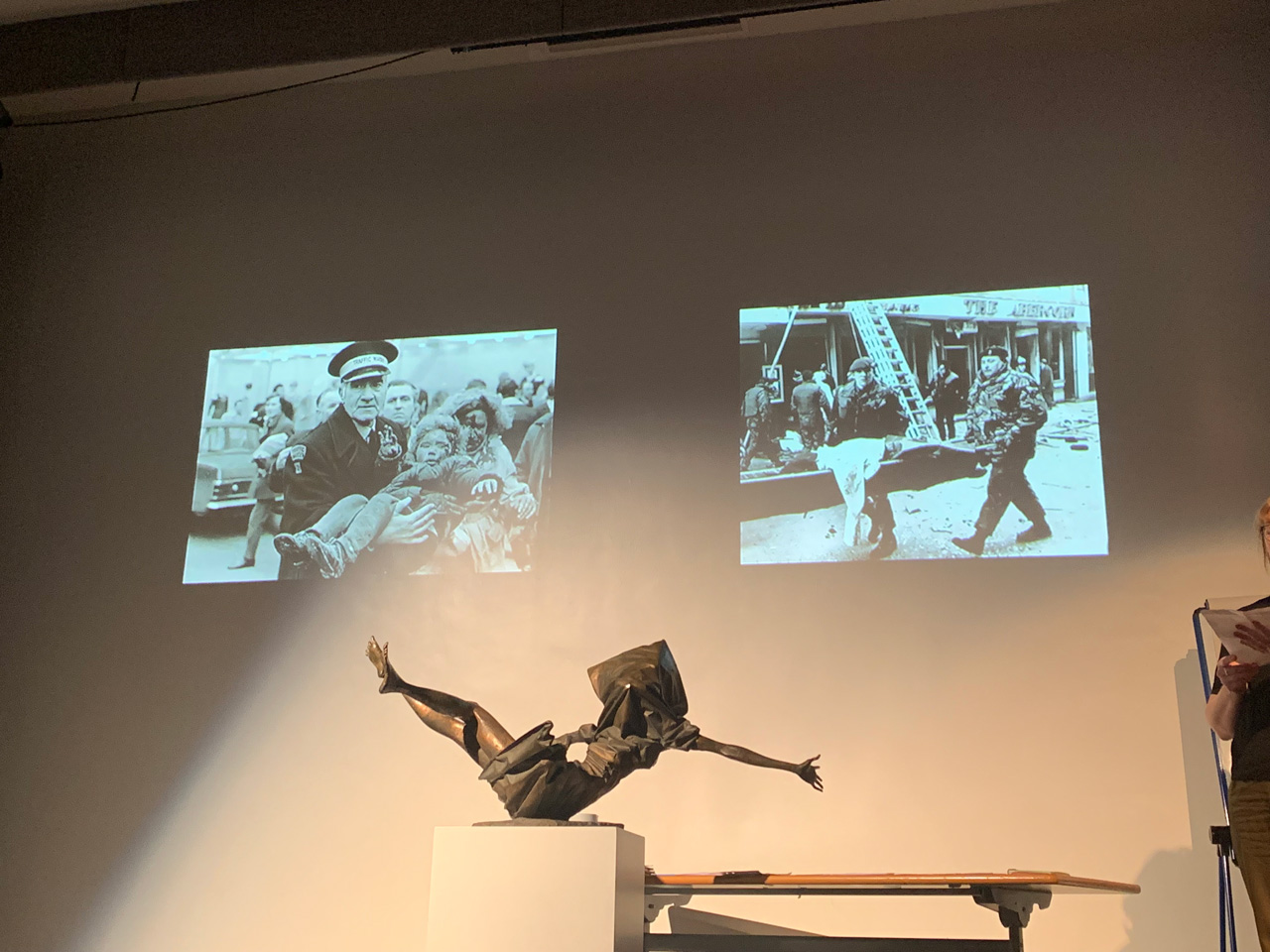

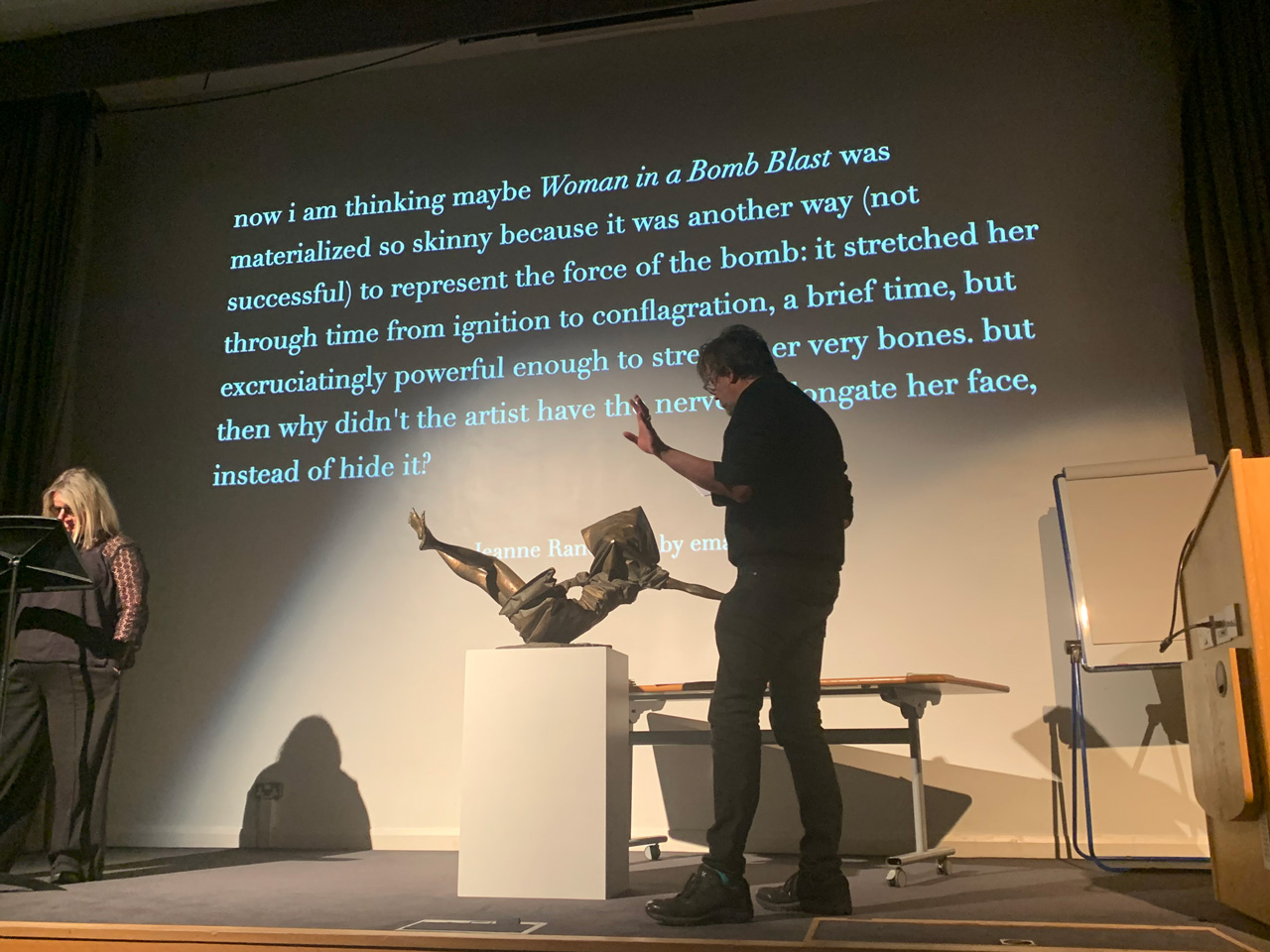

FE McWilliam, Woman in a Bomb Blast, 1974, bronze

© The Estate of FE McWilliam; collection of the Ulster Museum;

photograph Daniel Jewesbury

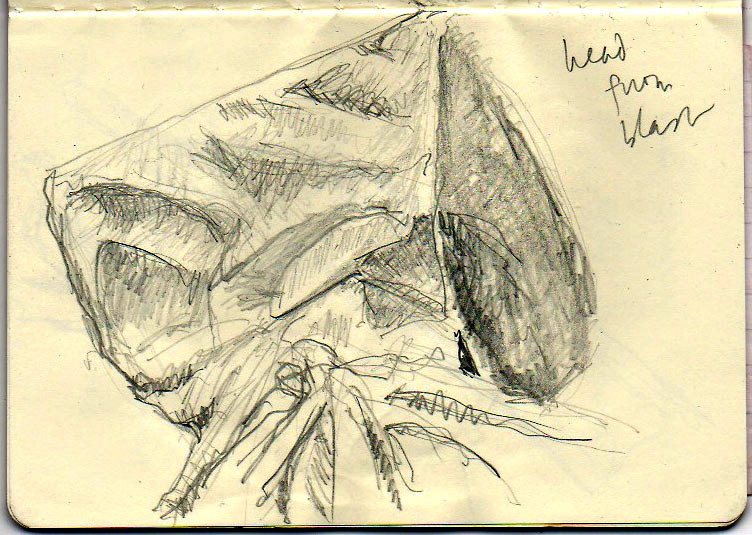

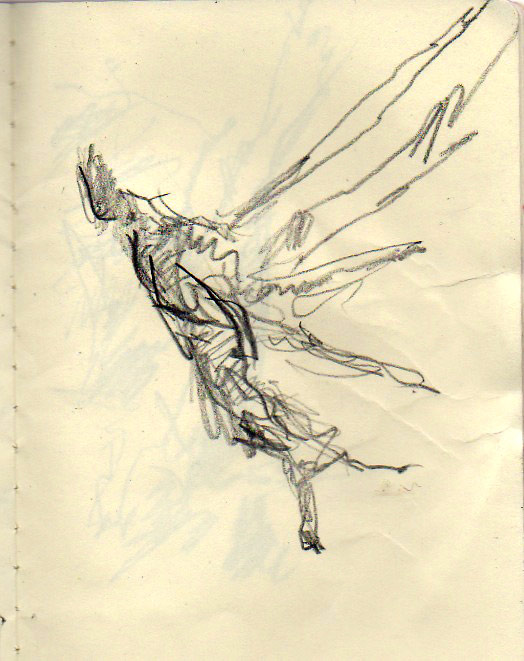

above & below: Daniel Jewesbury, Looking at the Woman in a Bomb

Blast, 2025, artist’s

book (Gothenburg: ArtMonitor).

Book design and cover collage by Alexandra Papademetriou

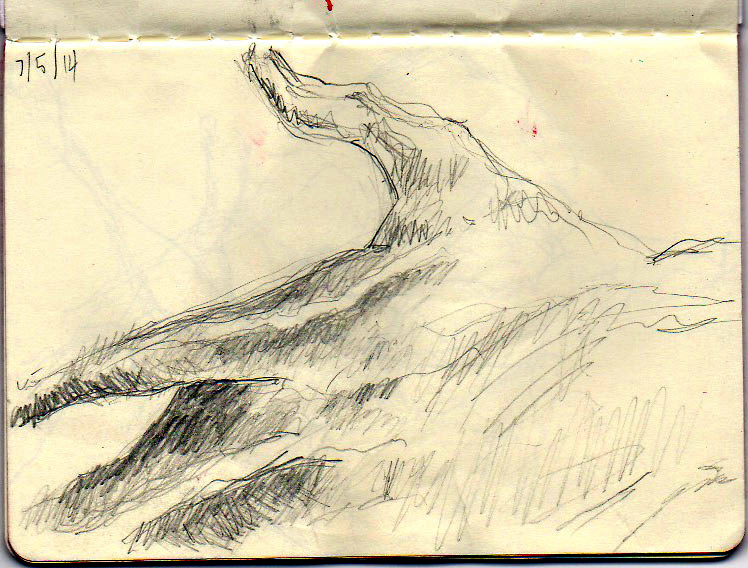

I’ve long been fascinated by this sculpture, for many reasons, and developed a response to it in performance when invited to contribute to the Ulster Museum’s major ‘Art of the Troubles’ exhibition in 2014. I had been drawing the sculpture for around 15 years, as a way of making myself look at it and think about its meanings.

For this work, I visited the gallery on a number of occasions, spending several hours at a time drawing the work from different angles. As I drew, links and references occurred to me and I noted these down; visitors to the exhibition also stopped to talk about the piece and their own relationship with it. I thought of paintings by Fragonard, Boucher (also here) and Courbet, sculptural nudes from Canova to Daniel, Clésinger and Rodin, and I researched the scrapbooks and drawings of McWilliam himself, reviews of the piece that were written in the art press in the mid-1970s, and I incorporated exceprts from Baudelaire's great work on death and desire, ‘Les Fleurs Du Mal’, and from works by Seamus Heaney.

Looking at the Woman in a Bomb Blast.

Performance as part of the Ulster Museum’s ‘Art of the

Troubles’ exhibition, 5 June 2014. 33'.

Filmed by Will McConnell and Neal Hughes. Use the video controller to

view in full-screen mode.

McWilliam’s work combines his fascination with sexuality and sculptural form in the somewhat awkward subject of a woman being blown forcefully backward by a bomb blast. The event which drove McWilliam to make this work was the bombing of the Abercorn Tea Rooms, in Belfast, on 4 March 1972. McWilliam was born in County Down, although he left Ireland in his teens. This and the series of smaller bronzes, ‘Women of Belfast’, which he made on the same theme, are the only pieces in which McWilliam made explicit reference to the Troubles.

The woman’s face is covered by a newspaper that has been blown across her face by the force of the blast. She has lost her balance, and struggles to catch hold of something. Her young, lithe limbs flail; the viewer is invited to look at her, and to enjoy looking at her, from various angles — we find ourselves looking uncomfortably up her skirt. Violence, desire, and a history of gesture are combined, but with shocking effect.

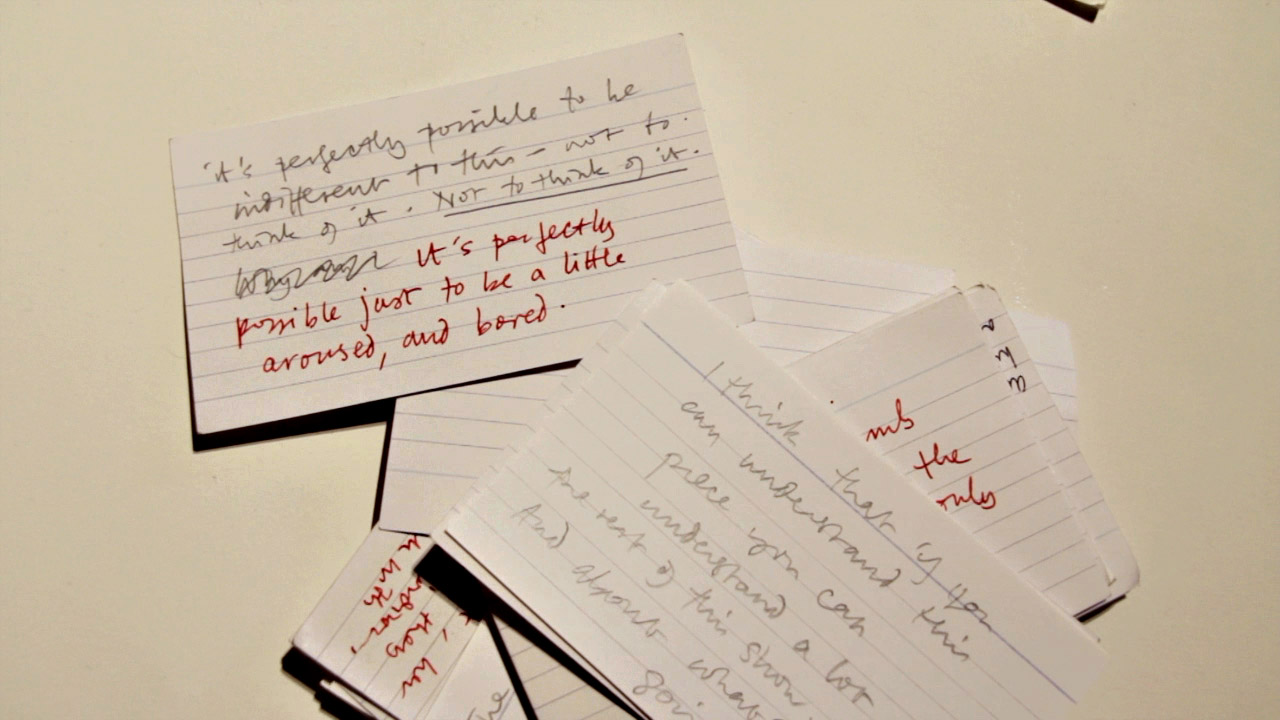

The large range of visual and textual materials that I gathered together for this work led me to turn the project into an artist’s book. This project began in around 2016, and developed very slowly, in libraries, museums and archives, in residencies at the Centre Culturel Irlandais and the Institut Suèdois in Paris, and in writing retreats near Gothenburg. The first full draft of the text was finally completed in July 2023. The book sits, somewhat uneasily, between George Bataille’s ‘Tears of Eros’, Aby Warburg’s ‘Mnemosyne Atlas’, and a pornographic surrealist novella. It asks how to account for the way the sculpture simultaneously compels us to look at it, and repels us, making us feel guilty for doing so; and it explores the way obsession and a certain perverse relationship between artist, artwork and viewer structure not just this work, but all artwork.

As you walk along a street that’s been familiar to you for years, where every surface seems to reflect the heat of the sun and dazzle you a little, behind this next wall or this bush or tree there might be the scene of your most unconscious sexual fixation, and all you will see is a glimpse before the moment will be lost again: perhaps someone you know will call out to you, or a car will crash behind you, or a doorbell somewhere will ring, or the sunlight reflected in an apartment window will distract you. By the time you get to look again, it’s gone, whatever it was. Perhaps all you saw was a piece of clothing of a specific colour, against skin of a certain shade, or a pose, or a look, straight back at you, or hair the colour or cut of someone lost to you for decades but in you all this time, a young woman or an older man or even a small boy. The glimpse aroused in you a desire that you cannot even understand because you can’t register it, you can’t check again, you cannot confirm this lust. It remains, unpurgeable, ungraspable, when you close your eyes, there when you try not to think of it.

Performance at the Ulster Museum, Belfast, 2014. Photo Neal Hughes

I, on the contrary, remain frozen, still, for you to look at. For you to appreciate me. I am a moment, a glimpse, made lifeless, in the very act of dying, at the most perfect moment of all, the most exquisite. For you to stare at, if you dare. Mostly, this doesn’t happen, since looking in a museum is always looking in front of others. In the museum, you look, looking at others who are looking at how you look. You are self-conscious. You would love to look at me, but it seems too indecent. So here I am, a glimpse presented just for you to enjoy, and you can’t, because you won’t, for the shame of it.

Performance at the Ulster Museum, Belfast, September 2021. Photos Anna Liesching

© Daniel Jewesbury